It’s been months since I visited Chad Holdorf, the agile “ninja” who walks the halls of the John Deere Intelligent Solutions Group (ISG) in Des Moines. Chad also influences all of ISG organization out to Illinois, Germany, India, and more, affecting at least 1200 people.

It’s been months since I visited Chad Holdorf, the agile “ninja” who walks the halls of the John Deere Intelligent Solutions Group (ISG) in Des Moines. Chad also influences all of ISG organization out to Illinois, Germany, India, and more, affecting at least 1200 people.

When I think back on my experience, I’m still in awe. I’m almost speechless. There’s a powerful fire that’s been lit in the minds and hearts of this tractor company and it is being beautifully fueled and maintained. Chad introduced me to coaches he’s brought in to help their unusually successful transition from traditional “waterfall” development practices towards a more agile approach. I met managers and developers he’s inspired and motivated. I even spoke to non-developers who have been impacted. After seeing the improvements, and the fun!, it’s hard not to just wax so effusively that I sound like a crazed rock star groupie. Luckily, time has helped me reflect and be more coherent about what I discovered there.

First of all, a word from our sponsors. One of my mentors, Christopher Avery, introduced me to Chad. Christopher Avery teaches a profound understanding of how to be a leader in your own life and have greater impact on others with more responsibility, effectiveness, and power through his Leadership Gift program. I’d also like to thank my employer, SAP, for their support in making the visit possible. As John Deere is a customer of SAP (as is so much of the rest of the companies on this small blue orb) I could learn how SAP was benefiting John Deere at that location, and how we could benefit them even more, as well as bring back some of the Agile Goodness being spread around John Deere ISG.

Ok, now back to our program. To summarize in bullets, this is what I saw.

- Meaningful work

- Catalyst Leadership

- Servant Leadership

- Play

- Vulnerability

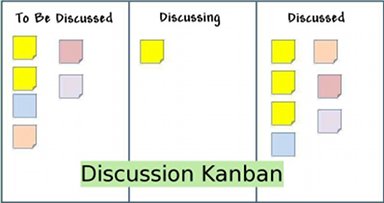

So what exactly did I see? The Intelligent Solutions Group provides the brains for tractors and online presence for John Deere. In Des Moines, I got to witness the tail end and beginning of an eight week cycle where all the teams come together to look at what they’ve done, ship something to their stakeholders, and plan the next cycle. Chad also invites representatives from other companies working on agile transitions to view what ISG has done, as well as share their own agile transition processes. More on that later.

Meaningful Work

Chad talks about this right away and even shared with me some of the slides he shows when he starts to talk about what they’ve done. John Deere helps feed the planet. The population of our planet has been growing and is expected to grow much more. The people at John Deere know they make a difference and it shows in their enthusiasm for making things better.

Servant Leadership

Even if you’re not familiar with the late Robert K. Greenleaf’s book of the same name, it’s unlikely you’ve not heard this term. The executive team at John Deere have provided ample support to Chad, letting him introduce unconventional practices. They continue to empower him to make a difference. They keep saying yes, providing funds for coaches, equipment, furniture, and trainings. They’ve not needed to take the credit. Chad too embodies this. He doesn’t have an office. He has no one reporting to him. And he was excited to see others be brilliant in the company, encouraging colleagues to bring in new practices that constantly improve their processes.

Catalyst Leadership

This is a term I first encountered at Agile 2008 in Toronto from the book Leadership Agility by Bill Joiner. But it’s also a term used in the book The Starfish and the Spider, a book about the power of leaderless organizations. Chad has no authority to command obedience, yet he personally and single handedly took on the responsibility for making his entire division jump on board the Agile train. How does Chad catalyze instead of control?

Play

This paragraph will be hard for me to keep short. One of the first things that Chad showed me on arrival was pictures of him covered in mud and dressed up as Forrest Gump when he ran a crazy mud drenched race that required him being hosed off afterwards. He brought that level of fun to his work the whole day. Look what cool things are happening here! Look at the crazy challenges we’ve overcome. It was fun for him that ISG has 50% less warranty claims, 7% higher employee engagement, but even more fun for Chad was seeing how awesome things were happening that he had nothing to do with. Chad uses fun to teach agile practices. Instead of a boring powerpoint presentation, Chad bought hundreds of dollars of legos himself and brings it to groups from 20 to 200+ and tells them to build a city. Then they learn Scrum, Scrum of Scrums, and other agile practices to build their lego metropolis.

Vulnerability

Rather than keep things secret, John Deere ISG courageously brings in agile practitioners in from many companies to see exactly what they’re doing. Chad is open and frank about their challenges, and humble. The Brene’ Brown book, The Gifts of Imperfection, helped me understand the power of not just what they’re doing by letting others come visit them, but why. Even though they call it a benchmarking process, there wasn’t a lot of time spent comparing. There was much more time sharing and collaborating with how both John Deere and SAP could do better. Chad’s incredible openness engenders courage and trust in his own company, as well as in others. According to Brene’ Brown, letting go of comparison helps cultivate creativity. And there was much of that evident, including really fun product demos made by teams to show off their work the last 8 weeks.

Conclusions

Conclusions

The conclusion is I’m not done pondering or thinking about Chad Holdorf’s work. I got to meet him again in Dallas at the Agile 2012 conference, learned more about his dreams and aspirations for himself, John Deere, and the software industry. He’s definitely someone to watch out for. If you’re interested in learning more, or maybe applying to be one of the fortunate companies to witness the power of what they’re doing there, feel free to email me and I’ll put you in contact. And take a look at some of these other blog posts and articles praising Chad’s work at John Deere ISG:

Jim McCarthy, author of the

Jim McCarthy, author of the

Most of you are probably familiar with the adage, “Physician, Heal Thyself!” The miracle of internet search revealed to me that this actually came from the New Testament as a quote of Jesus from an even older proverb. The meaning might seem to be transparent, which is that healers should use their own knowledge on themselves before attempting to use it on others.

Most of you are probably familiar with the adage, “Physician, Heal Thyself!” The miracle of internet search revealed to me that this actually came from the New Testament as a quote of Jesus from an even older proverb. The meaning might seem to be transparent, which is that healers should use their own knowledge on themselves before attempting to use it on others.

becomes “explosive” after they try and fail to fulfill the assignment. Phaedrus is genuinely curious to get an answer and tries to find it with his students. Although Phaedrus confesses he does not know the answer, his students ask him about what he thinks about the question and he replies “I think there is such a thing as Quality, but that soon as you try to define it, something goes haywire. You can’t do it.” The name of Pirsig’s book was “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance”, with the subtitle “An Inquiry into Values”. Yes, values.

becomes “explosive” after they try and fail to fulfill the assignment. Phaedrus is genuinely curious to get an answer and tries to find it with his students. Although Phaedrus confesses he does not know the answer, his students ask him about what he thinks about the question and he replies “I think there is such a thing as Quality, but that soon as you try to define it, something goes haywire. You can’t do it.” The name of Pirsig’s book was “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance”, with the subtitle “An Inquiry into Values”. Yes, values.